I feared this day might come. Even though I have been working fastidiously on my upcoming D-Day book over the past several months, I have been absorbing the tragic yet unsurprising clash in Charlottesville, Virginia. As the plantation home of Thomas Jefferson, I have long thought of the place as an historic embodiment of the nation’s founding ironies—a society that precariously balanced republican virtues and enslavement. Further ironies have ensued as the picturesque college town turned into a battleground rocked by the fury of racial animus. The American Civil War is still claiming lives; it has never ceased extinguishing life.

While scores have found the recent events in Virginia

shocking, I have woefully been anticipating these happenings ever since the

shooting at the historic Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in

Charleston, South Carolina in 2015. (Read my reflection on that incident here.)

The subsequent debate about the presence of the Confederate flag in public

spaces was only another aftershock of the conflict that nearly destroyed our

Union. And we have yet to feel the last reverberation of that war.

Quite naturally, Confederate monuments have become the

centerpieces of the ongoing debate to determine what we commemorate in

this country. Let us first contemplate the patterns and motivations of these

memorials. The peak of Confederate monumentation was the 1890s through the

1920s when substantial numbers of Civil War vets were still alive and civically

active. Many of the ones dedicated in the 1910s and 1920s were underwritten by

Klansman during their resurgence after the debut of The Birth of a Nation.

Such memorials included an iconic rock carving of Lee, Davis, and Jackson on the

mammoth Stone Mountain outside Atlanta. (A popular amusement park now sits

beneath the sculpture.)

A lesser but still significant batch of monuments were

dedicated in the 1950s and 1960s in the face of integration—many of them in

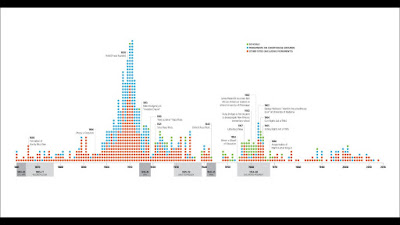

front of schools, serving as a figurative middle finger to Brown v. Board of Education. These also coincided with the overlapping Civil War centennial. An acquaintance sent me the chart

below revealing trends in memorials to Confederate soldiers. It is not

difficult to recognize that many of these memorials (though I am sure not all)

were in reaction to advancements in civil rights and a yearning for a Lost

Cause Eden among white southerners.

Fellow scholars of the Civil War—ones far better known than me—have been making the rounds on talk shows to offer context to the perturbed and often ill-informed masses. Historian David Blight is among those historians speaking up. When asked if we are on our way to another internal war, Blight suggested we keep an eye out for other forms of disunion: the disintegration of political parties, the rise of the Alt-Right, people’s intolerance for facts and the historical record.

In an interview for the New

Yorker, Blight noted that earlier episodes in American history such as the

Mexican War, vigilante justice, and abolitionist John Brown’s 1859 raid were

triggers that sparked the larger confrontation to come. “No one predicted them.

They forced people to reposition themselves,” Blight said. “We’re going through

one of those repositionings now. Trump’s election is one of them, and we’re

still trying to figure it out. But it’s not new. It dates to Obama’s election.

We thought that would lead culture in the other direction, but it didn’t,” he

said. “There was a tremendous resistance from the right, then these episodes of

police violence, and all these things [from the past] exploded again. It’s not

only a racial polarization but a seizure about identity.” President Trump’s

quiet acceptance of Confedefascists and his enthusiasm of spurring violent

attitudes at rallies make him an accessory if not an instigator. His inability

to promptly condemn ideologically-driven violence as quickly as he condemns—well,

anything else—is astounding.

I have been reading the comments of many on social media who indicate a fear that

Confederate monuments will be removed from battlefields and national parks next,

and that the social justice warriors will have stepped too far once again. I

think it is a debate that will vigorously emerge as the bronze generals

and rebels begin to domino.

As someone who lived and worked on the Gettysburg battlefield

for several years, it is hard for me to imagine such a place without monuments

standing to both sides. With a few exceptions early on, I rarely thought of southern

monuments as anything more than three-dimensional visualizations of battle.

Silhouetted against a summer sky, the statues are stirring and make for vibrant

postcard images. I daily passed many of them on my way to work.

But as is the case with most interpretations of the past,

ulterior messages reveal themselves. The 1917 dedication of Gettysburg’s

Virginia Memorial took place during World War and, in many ways, represented a

form of reconciliation between northerners and southerners on the hallowed

grounds. At the same time, the stains of slavery and the dramatic rewriting of

history marked the proceedings. Leigh Robinson, a Civil War veteran of a

Virginia artillery battery, said in his dedicatory comments: “Southern master

gave to Southern slave more than slave gave to master; and the slave realized

it. Better basis for the uplift of inadequacy can no man lay than is laid in

this. This slavery was the school to redeem from the sloth of centuries.” In

this context, it is impossible to separate the war from the warrior.

Singular Confederate monuments on courthouse greens or town

squares usually only tell one side of a story—and often do so inaccurately.

Even if tainted by the words that dedicated them, Confederate monuments facing Union monuments on battlefields fit within a

broader narrative of states, nations, and ideals in conflict with each other. This is an important fact to remember.

Memorials observing the Civil War era have been points of

contention on smaller levels for years. I personally think the interpretation of the Heyward Shepherd monument at Harpers Ferry is a thorough means of

telling two sides of an otherwise one-sided story. At the same time, I can

recognize that a side street tablet is not the same as a towering equestrian statue in a city park. I equally

recognize that many citizens do not want context but justice, if not vengeance.

At this hour of tension, however, we might be prudent to

reflect upon the words of Robert E. Lee himself. In writing to an associate in

1869 regarding the potential for Confederate monuments, he wrote, “I think it

wiser, moreover, not to keep open the sores of war, but to follow the example

of those nations who endeavored to obliterate the marks of civil strife, and to

commit to oblivion the feelings it engendered.” Even the man who spearheaded

some of the Confederacy’s most stupendous military achievements later

recognized that memorials to the failed rebellion would only serve as open wounds.

The removal of Confederate memorials is unlike the fears associated with dismantling memorials to the Founding Fathers. The founders forged an imperfect republic that they hoped future generations would have the wisdom to correct and adapt. The Confederacy sought instead to build upon America's moral flaws rather than its strengths while simultaneously undermining the democratic process.

The removal of Confederate memorials is unlike the fears associated with dismantling memorials to the Founding Fathers. The founders forged an imperfect republic that they hoped future generations would have the wisdom to correct and adapt. The Confederacy sought instead to build upon America's moral flaws rather than its strengths while simultaneously undermining the democratic process.

The Southern Poverty Law Center recently started a petition which states, “More than 1,500 Confederate

monuments stand in communities like Charlottesville with the potential to

unleash more turmoil and bloodshed. It's time to take them down.” Going by the

Confederate monument map below, that will be a very difficult endeavor. Perhaps some should come

down; perhaps others should remain. Whichever way you feel, I believe it a

conversation worth having if we ever wish to outrun the malevolent shadows of

the war.

I find myself an intrigued observer to the process. I can recognize monuments as historical relics just as I can German bunkers in Normandy. They tell a story of a certain place, time, and condition. I can also recognize memorials as forms of public art. On the flip side, there is a stark contrast between observation and celebration. Indeed, Confederates can be recognized for their bold military maneuvers. They can also be recognized as being on the wrong side of history. Many Americans are incapable of recognizing this because they cannot separate themselves from their ancestors. The actions of our ancestors should not be reflected on us.

Ultimately, I find the impromptu

demolition of Confederate memorials in places like Durham, North Carolina as

unhelpful and dangerous. Such acts only embolden white nationalists who seek

to use such monuments as a platform for spewing their vitriol. Nor can we dismantle places like Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial overlooking the national cemetery. But we can revisit and reanalyze them. If citizens wish

to remove a Confederate monument, they should do so peaceably and diplomatically

by campaigning to their elected leaders, using historical evidence and

passionate moral rationale as their basis. The Southern Poverty Law Center lists a number of useful strategies to fight hate smartly and peacefully.

As these matters continue to unfold, historians reveal

little surprise in the resurgence of hate groups in the wake of nation’s first

African American president. The trend represents a desperate, final struggle to

maintain a misguided nostalgia and mindset of the 19th century.

Several months ago, director Rob Reiner vocally declared that the current state

of affairs represented the last battle of the Civil War. I do not disagree. We

find ourselves amidst a new civil war, one not as lethal or well-defined as

that of the 1860s, but an ongoing cultural struggle to define or redefine what

we represent. But those definitions were never clear from the outset.

As one friend suggested, the struggle now is not between North and South, but between urban and rural. The 2016 election map by county suggest as much. We have a long way to go in mending those fences.

As one friend suggested, the struggle now is not between North and South, but between urban and rural. The 2016 election map by county suggest as much. We have a long way to go in mending those fences.

This fall semester I am teaching a

course on the Battle of Gettysburg in history and memory. We examine not only

the men, their maneuvers, and their motivations but also what Gettysburg and

the Civil War have represented to we as a people. If

the commentary above is indicative of anything, it proves that there are many

ways to ponder those themes. In this era of “alternative facts,” it is all the

more important we examine the historical record for what it truly is. I do not

think I will have any difficulty imparting the relevance and emotion of the

Civil War to my students this semester.

No comments:

Post a Comment