I recently read this article in the Reading Eagle. It discusses a recent event hosted by the First Defenders Civil War Roundtable in the Reading, PA area. Civil War sage Ed Bearss was the meeting's guest speaker. Some of Bearss's claims raised some interesting questions in my mind. Where was Lee possibly going during the Gettysburg Campaign? Click on the above map to see just some possible targets.

The capitol in Harrisburg was the big prize. Fear was felt throughout the city, evident in the construction of Fort Couch constructed on the outskirts of the capitol. Some 1800 free blacks and Pennsylvania Railroad workers built it and another fort throughout late June 1863. Obviously, the U.S. Army facilities in Carlisle and the need to capture the Columbia/Wrightsville Bridge were tempting sub-targets along the way. Luckily for the people of Harrisburg, the bridge was burned by militia and the townspeople before John B. Gordon and his Confederates could cross the mile-wide covered bridge across the Susquehanna River. As Bearss argues in the above article, Lee (or a portion of his forces) may have continued into the Anthracite coal regions of eastern PA should he have captured Harrisburg.

What about Philly? There were innumerable munitions depots in addition to the Philadelphia Naval Yard, which constructed blockaders and Union ironclad gunboats. The Philadelphia Troop even ventured westward to encounter advancing Confederates but quickly turned tail at one of the first signs of resistance (a fact absent in the troop's Philadelphia museum). Some of them did help destroy the Wrightsville Bridge though.

U.S.S. New Ironsides was launched in 1862 by Merrick & Sons at the C. H. and W. H. Cramp shipyard in Philly.

The target of Washington was always fool's gold for Confederates I believe, especially by 1863. The city was the most fortified in the world. Lincoln's paranoia of the constant defense of the capitol sometimes constricted the Union's army flexibility, but in cases such as this, certainly may have helped. Baltimore as a target introduces new aspects as well. Given the secessionist fervor that was always present in the city, might have Lee been greeted as a liberator rather than an invader?

Fort Stevens was one of the 75 plus forts encircling Washington.

I think the true "eight ball" of potential targets rest not in the east, but in the west. The Pennsylvania heartland and industrialized west were perhaps even more vulnerable than the east. This too was an apparent fear, as seen in the trenches constructed in the Snake Springs Gap near Everett (then Bloody Run), Pennsylvania. Colonel Jacob Higgins, formerly of the 125th Pennsylvania, was on leave from duty in the summer of 1863. Upon hearing of the invasion, he quickly mustered railroad workers from Altoona, clerks from Hollidaysburg, and farmers from Bedford to prepare the defense of Central Pennsylvania. Several rings of redoubts were constructed in the hills of Bedford County should the southerners break through in the east. Many of these trenches are still standing and others have yet to be found.

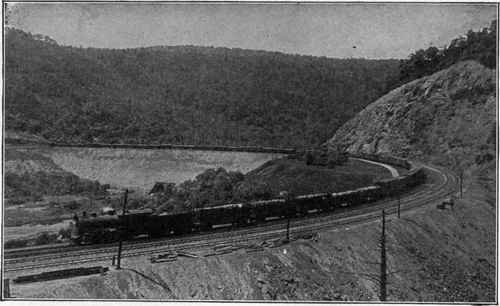

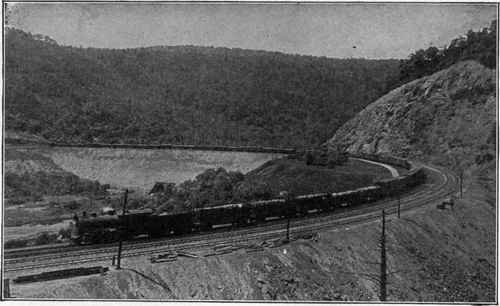

What might have been the largest target in central PA? The Pennsylvania Railroad plants in Altoona. The City of Altoona was the largest industrial railroad manufacturing center in the world at that time. The Civil War, in essence, made the PRR what it became. To destroy this hotbed of industry would have greatly crippled the Union war effort's ability to transport troops and munitions not only throughout the state, but throughout all the north and even portions of the south. The Horseshoe Curve, a massive railroad bend on the outskirts of Altoona, is still the main railroad artery which connects east and west in Pennsylvania. In 1942, Nazi agents attempted to destroy this site but were apprehended. The importance of this site would have been multiplied during the Civil War since there were no trucks or aircraft. The Curve was guarded during both wars but probably would have been very vulnerable amidst a coordinated attack.

The Horseshoe Curve

Johnstown was also along the path to Pittsburgh. Located there was the Cambria Ironworks, one of the largest iron and steel mills contributing to the Union war effort. Much like Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, the town was entirely surrounded by massive cliffs and hills and would have been impossible to defend. These hills nevertheless brought danger and death twenty six years later when they created a funneling affect during the infamous Johnstown Flood of 1889. (This deluge all but destroyed Cambria Ironworks).

Cambria Ironworks in Johnstown.

This ultimately leads us to the Pittsburgh area and Bituminous Coal regions of Western PA. There were dozens of mills, foundries, factories, railroad junctions, and industrial centers. Not to mention three massive rivers vital to the transportation of the war materiel produced there. Perhaps most importantly, the Allegheny Arsenal was one of the largest such facilities in the nation. It produced 14 million rounds of ammunition annually. The nearby Fort Pitt Foundry produced 15% of the total U.S. wartime artillery production. Imagine if the Confederates had captured these!

Heavy Artillery in front of Allegheny Arsenal

At least three forts were built around Pittsburgh during the Gettysburg Campaign. They included Fort Robert Smalls, Fort Laughlin, and Fort Jones. All were built on high ground overlooking parts of the city. In the following video, historian Michael Kraus tells us of these forts and the threats on Pittsburgh.

As you have already guessed, there was a multitude of targets throughout Pennsylvania. I did not even mention the plethora of agricultural communities, mills, kilns, foundries, canals, railroads, mines, and other centers of industry dotted throughout the smaller communities of the state. What about the oil drills in Titusville and Pit Hole northeast of Pittsburgh? Who knows? In the long run, most of these potential targets never became a reality for Robert E. Lee. Nevertheless, pointing them out reveals their importance during the war and just how badly the agrarian South fared against the mighty industrialized North.

Lee had eye on Berks, Schuylkill before he lost at Gettysburg, historian saysSo which is it? Was Lee heading toward Harrisburg (which seems most likely), but what after that? West into the heartland and Pittsburgh or east toward Philadelphia or the Washington region? For some, in retrospect, it may be easy to conclude where Lee was heading. In 1863, however, the entire commonwealth was in an uproar. Nobody knew where the Confederates were heading. Perhaps their forces would be split and head in different directions. Lee was not afraid to do this in the past. Lets take a look at a few possible objectives.

Imagine that Gen. Robert E. Lee and the Confederate army had won at Gettysburg.

In all likelihood, Lee would have moved on to complete his mission of sacking Harrisburg. After conquering the state capital, the Confederates probably would have continued heading east to raid farms in Berks County and take over the coal mines of Schuylkill County.At least that's what noted Civil War author and historian Edwin C. Bearss believes was Lee's intent for the Keystone State.

Bearss, who at 86 still tours the country to talk about the Civil War, recently spoke before the First Defenders Civil War Roundtable in Richmond Township.

Before his talk in The Inn at Moslem Springs, the Arlington, Va., resident spoke about the role southeast Pennsylvania played in the Civil War.

This region had strategic importance to Lee and his army, Bearss said. Farms would have supplied corn and cattle for Confederate troops, while the coal mines would have provided a ready supply of fuel for military uses.

"If Lee had been victorious, this is one of the areas he would have moved into," Bearss said of Berks County.

Of course, the question of what Lee would have done following a victory at Gettysburg in 1863 is purely academic.

The Confederate defeat in Gettysburg was a watershed moment in the war and shifted the momentum to the Union side.

Gettysburg was important to Pennsylvania on a number of levels, Bearss said. It was the only major conflict in the state, and Pennsylvania had a large concentration of troops in the battle.

"Pennsylvania, next to New York, would have been the most important state in both industry and providing troops," he said. "At Gettysburg, one-third of the troops there were from Pennsylvania."

Bearss was invited to Berks to speak during a meeting of the First Defenders, a Berks County group that meets to study and discuss the Civil War, said Joseph E. Schaeffer, group president.

At their monthly meetings, members try to have a featured author or historian talk about an aspect of the war.

At the same time, the First Defenders raise money to put toward land preservation efforts for Civil War battlefields and historic sites.

With the 150th anniversary of the Civil War coming in 2011, preserving the battlefields should be foremost on people's minds, Bearss said.

Keeping those hallowed grounds as open space available to the public is a fine way to remember the men who fought and fell, he said.

"The time to protect those lands is now," he said.

Contact Darrin Youker: 610-371-5032 or dyouker@readingeagle.com

The capitol in Harrisburg was the big prize. Fear was felt throughout the city, evident in the construction of Fort Couch constructed on the outskirts of the capitol. Some 1800 free blacks and Pennsylvania Railroad workers built it and another fort throughout late June 1863. Obviously, the U.S. Army facilities in Carlisle and the need to capture the Columbia/Wrightsville Bridge were tempting sub-targets along the way. Luckily for the people of Harrisburg, the bridge was burned by militia and the townspeople before John B. Gordon and his Confederates could cross the mile-wide covered bridge across the Susquehanna River. As Bearss argues in the above article, Lee (or a portion of his forces) may have continued into the Anthracite coal regions of eastern PA should he have captured Harrisburg.

What about Philly? There were innumerable munitions depots in addition to the Philadelphia Naval Yard, which constructed blockaders and Union ironclad gunboats. The Philadelphia Troop even ventured westward to encounter advancing Confederates but quickly turned tail at one of the first signs of resistance (a fact absent in the troop's Philadelphia museum). Some of them did help destroy the Wrightsville Bridge though.

U.S.S. New Ironsides was launched in 1862 by Merrick & Sons at the C. H. and W. H. Cramp shipyard in Philly.

The target of Washington was always fool's gold for Confederates I believe, especially by 1863. The city was the most fortified in the world. Lincoln's paranoia of the constant defense of the capitol sometimes constricted the Union's army flexibility, but in cases such as this, certainly may have helped. Baltimore as a target introduces new aspects as well. Given the secessionist fervor that was always present in the city, might have Lee been greeted as a liberator rather than an invader?

Fort Stevens was one of the 75 plus forts encircling Washington.

I think the true "eight ball" of potential targets rest not in the east, but in the west. The Pennsylvania heartland and industrialized west were perhaps even more vulnerable than the east. This too was an apparent fear, as seen in the trenches constructed in the Snake Springs Gap near Everett (then Bloody Run), Pennsylvania. Colonel Jacob Higgins, formerly of the 125th Pennsylvania, was on leave from duty in the summer of 1863. Upon hearing of the invasion, he quickly mustered railroad workers from Altoona, clerks from Hollidaysburg, and farmers from Bedford to prepare the defense of Central Pennsylvania. Several rings of redoubts were constructed in the hills of Bedford County should the southerners break through in the east. Many of these trenches are still standing and others have yet to be found.

What might have been the largest target in central PA? The Pennsylvania Railroad plants in Altoona. The City of Altoona was the largest industrial railroad manufacturing center in the world at that time. The Civil War, in essence, made the PRR what it became. To destroy this hotbed of industry would have greatly crippled the Union war effort's ability to transport troops and munitions not only throughout the state, but throughout all the north and even portions of the south. The Horseshoe Curve, a massive railroad bend on the outskirts of Altoona, is still the main railroad artery which connects east and west in Pennsylvania. In 1942, Nazi agents attempted to destroy this site but were apprehended. The importance of this site would have been multiplied during the Civil War since there were no trucks or aircraft. The Curve was guarded during both wars but probably would have been very vulnerable amidst a coordinated attack.

The Horseshoe Curve

Johnstown was also along the path to Pittsburgh. Located there was the Cambria Ironworks, one of the largest iron and steel mills contributing to the Union war effort. Much like Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, the town was entirely surrounded by massive cliffs and hills and would have been impossible to defend. These hills nevertheless brought danger and death twenty six years later when they created a funneling affect during the infamous Johnstown Flood of 1889. (This deluge all but destroyed Cambria Ironworks).

Cambria Ironworks in Johnstown.

This ultimately leads us to the Pittsburgh area and Bituminous Coal regions of Western PA. There were dozens of mills, foundries, factories, railroad junctions, and industrial centers. Not to mention three massive rivers vital to the transportation of the war materiel produced there. Perhaps most importantly, the Allegheny Arsenal was one of the largest such facilities in the nation. It produced 14 million rounds of ammunition annually. The nearby Fort Pitt Foundry produced 15% of the total U.S. wartime artillery production. Imagine if the Confederates had captured these!

Heavy Artillery in front of Allegheny Arsenal

At least three forts were built around Pittsburgh during the Gettysburg Campaign. They included Fort Robert Smalls, Fort Laughlin, and Fort Jones. All were built on high ground overlooking parts of the city. In the following video, historian Michael Kraus tells us of these forts and the threats on Pittsburgh.

As you have already guessed, there was a multitude of targets throughout Pennsylvania. I did not even mention the plethora of agricultural communities, mills, kilns, foundries, canals, railroads, mines, and other centers of industry dotted throughout the smaller communities of the state. What about the oil drills in Titusville and Pit Hole northeast of Pittsburgh? Who knows? In the long run, most of these potential targets never became a reality for Robert E. Lee. Nevertheless, pointing them out reveals their importance during the war and just how badly the agrarian South fared against the mighty industrialized North.

No comments:

Post a Comment