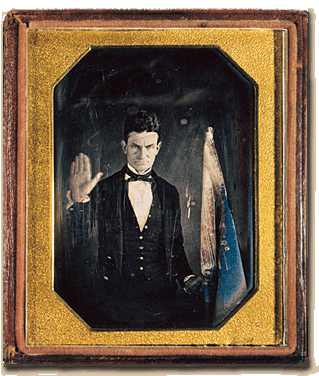

Abolitionist John Brown was hanged for treason 150 years ago this Wednesday. Was he terrorist or hero? Maybe both. Let us examine what led to his demise.

Abolitionist John Brown was hanged for treason 150 years ago this Wednesday. Was he terrorist or hero? Maybe both. Let us examine what led to his demise.“I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood” (Hearn 39). The fiery, fifty-nine year-old abolitionist wrote these impending words only hours before he was to be hanged for treason, murder, and inciting insurrection. Only six weeks earlier, the man had been on the verge of successful revolution, a rebellion he envisioned would forever change the course of slavery in

The beginnings of the attack originated over a year before the initial raid. John Cook, one of Brown’s faithful disciples, found housing and employment in the sooty industrial town of

Old Man Brown, “Captain Isaac Smith,” arrived in nearby

By mid-October, Brown felt the time for action had come. On the night of the sixteenth, he walked into the Kennedy Farmhouse and confidently stated, “Men, get on your arms. We shall proceed to the Ferry.” The army of eighteen solemn men stockpiled weapons in a wagon and set forth in the chilled October mist at approximately

Brown’s master plan soured quickly as the night progressed. A series of colossal errors turned the tables on him and his followers. One of the town’s night watchmen, Patrick Higgins, freed himself from the grip of his abolitionist captors. Higgins halted an approaching Baltimore & Ohio locomotive and warned its passengers of the potential danger. This uproar sparked the curiosity of Hayward Shepherd, the station’s baggage master. John Brown’s son, Owen, saw Shepherd’s silhouette approaching him. When Owen ordered the man to halt, Shepherd fled with haste toward the town. Brown fired his carbine, and a bullet ripped through the escapee’s body. Shepherd slumped onto the train platform, his blood pouring onto its wooden planks. In this unfortunate mortal wounding lies one of the great tragic ironies of the raid. Hayward Shepherd was a free black man (Frye 19).

These shots echoed like thunder in the quiet dead of night. Dr. John Starry rose from his bed and slipped into the darkness to reconnoiter the chaotic situation. The raiders immediately seized Starry and, when learning he was a physician, quickly summoned him to the hemorrhaging Shepherd. When nothing else could be done for the slain baggage master, Brown himself committed a fatal error; he let the doctor go. Starry, later recognized as the “Paul Revere of

Furthermore, Brown allowed the B&O passenger train to continue to its destination. The conductor of that train telegraphed for military aid at the next station. This combination of errors led to the ringing of alarms throughout the valley. Hundreds of local militia answered the call. This summon for troops was the beginning of the end for Brown’s hopes of tactical victory. Within hours, the “steel trap” which Douglass warned of was about to snap (Frye 20). The abolitionists were completely penned in. The question is, were they prisoners because of fate or prisoners of choice? Did Brown not attempt escape because he was physically trapped, or did he choose to stay in

October 17 resulted in a tense “no man’s land” atmosphere between the local militia and the raiders. The citizenry became further outraged when their unarmed mayor, Fontaine Beckham, was gunned down by a raider. Afterward, some of Brown’s men attempted to surrender and were promptly executed vigilante style. Dangerfield Newby, an African-American with Brown, was shot through the head with a railroad spike. Townspeople dragged his limp body away from the fighting. They then proceeded to slit his throat from ear to ear, cut off his genitals, poked sticks into his wounds, and sliced off his ears as souvenirs. Finally, they threw him in the nearby “Hog Alley,” where townspeople dumped their garbage for the pigs to devour. The people of

By the early morning hours of October 18, Colonel Robert E. Lee and ninety U.S. Marines arrived by train at the Ferry. As daylight ascended, Lee’s aide, Lieutenant J. E. B. Stuart, slowly approached the engine house to demand unconditional surrender. Brown replied he would rather die where he stood. With this, the young officer waved his hat in the air as a signal. Two dozen Marines immediately sprang forward. When they failed to collapse the door with a sledge hammer, a large ladder was implemented as a battering ram. A whole was punched in the wood large enough for one man to clamor through. Lieutenant Israel Green was first inside. Spotting Brown, he plunged his flimsy ceremonial sword into Brown’s stomach, hitting a belt buckle and bending his thin blade in half. Green then used the butt of his sword to smash Brown’s head to a point of near unconsciousness. The assault was over in three minutes. All eleven hostages were freed. The five remaining raiders were killed or captured (Hearn 31).

Why did Brown fail? The plan first began to tailspin when free black Hayward Shepherd was carelessly murdered by Owen Brown. Also, John Brown allowed the doctor tending Shepherd to flee, thus resulting in the first alarms of invasion. The killing of unarmed civilians brought the wrath of the locals upon the men of the Provisional Army. In addition, the raiders allowed for a full B&O train to proceed to its destination. Brown had no qualms with the passengers; therefore he let them go. The conductor on this train spread the word of invasion even further.

Brown also showed weakness and sympathy toward his captives. He allowed the families of his hostages to visit, and they gathered knowledge of the raiders’ strength and disposition. He exchanged hostages for hot breakfasts from the nearby Wager Hotel. He permitted hostages to leave and return (Hearn 32). Brown was infamous to some for his cold-blooded murders and hostility. Three years before

John Brown also chose a poor defensive position when it came to the final hours of his insurrection. He took refuge in a small engine house with high and few windows. The raiders were not even able to fire their weapons out these windows without piling items to stand on. His atmosphere became cramped, smoke-filled, and disorienting. Why he instead did not select a larger arsenal building stockpiled with weapons we will never know.

Finally, what became of the slaves, the slaves who would rush to Brown’s aid at his moment of greatest need? These freedom-seeking soldiers were to comprise the army intended to wreak havoc on the slaveholding South. What happened? The word never got out to them. Those slaves who heard of the raid once it was initiated feared repercussions. For those who may have been waiting in the surrounding

One week after the raid Brown faced a jury and was soon after found guilty of treason, murder, and insurrection. He was hanged one month later on

Works Cited

"The American Experience | John Brown's Holy War | People & Events | Henry David Thoreau." PBS. Web.

Cohen, Stan. John Brown: The Thundering Voice of Jehovah.

Frye, Dennis E. "Purged Away with Blood: John Brown's War." Hallowed Ground (Volume 10, No. 3. Fall 2009): 16-21. Print.

Hearn,

I recently learned that the original "John Brown's Body" was written about a Massachusetts soldier named John Brown, and that verses were later added referencing John Brown the 'Old Man.' I thought this to be very interesting! Did you make it to any of the sesquicentennial events in Harpers Ferry and Charlestown?

ReplyDeleteHi Dylan,

ReplyDeleteThat is pretty interesting.

I did in fact make it to the 150th anniversary of the raid. Go back a few posts on this blog to early November. I have a very large post on it with tons of photos and video. Thanks for your interest!